As part of the celebrations for the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death, the first comprehensive retrospective devoted to his teacher, Andrea del Verrocchio (1435‐1488), is now open at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, with a section at the Bargello Museum, and will travel (in part) to Washington’s National Gallery in the Fall of 2019. 120 works by Verrocchio, Leonardo, and their contemporaries illustrate the artistic output of Florence from 1460 to 1490 during the era of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

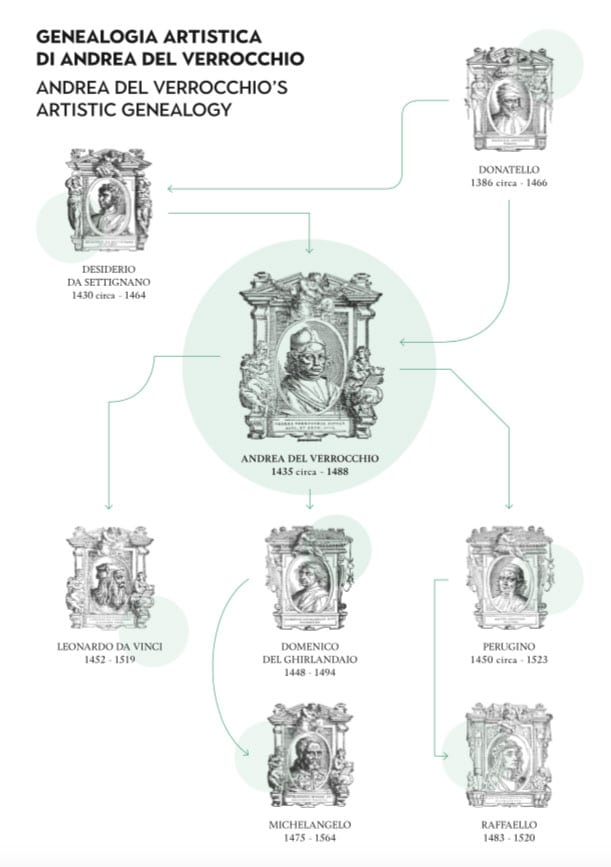

Great teachers are always remembered by their students, but aren’t always the best at their chosen profession. Think about it: maybe you’ve had a brilliant high school English teacher who really taught you how to structure an essay but never published any of her own, or a tennis instructor who finally explained the backhand to you, but didn’t rank top in his country’s competitions. Verrocchio, the polymath sculptor, painter, goldsmith and even architect, is that artist who was pretty good all round and taught a whole lot of great artists, including Leonardo, but perhaps spread himself too thin to garner critical fame. Trained as a goldsmith, he learned sculpture from Desiderio da Settignano and Donatello. He came to painting late, in the 1470s (he was already in his mid 30s) and Perugino and Ghirlandaio learned from him. The pupils of his pupils include no less than Raphael and Michelangelo. From a technical point of view, he must have been impeccable. In this show we see many works by members of Verrocchio’s large workshop and it often hard to tell what was his, contributing “to the negative criticism that blighted Verrocchio’s reputation.” The curators suggest that with the pupil, Leonardo, outshining the teacher, nobody has taken the time to assemble a retrospective show about Verrocchio… until now. The result? A good show that indeed sheds light on an artist that has always been on our radar, but never really under the microscope.

This exhibit is organized into eleven parts, nine of which are at Palazzo Strozzi, while two sections continue at the Bargello with works that could not be moved. The Bargello has generously loaned some of its most important works (Verrocchio’s David and the Lady with Flowers are arguably amongst the top pieces here), and other loans come from major institutions around the world. In the video below, I take you on a spontaneous walkthrough of the show that I created for Instagram IGTV and stories; the casual vertical format video gives you a quick 3-minute tour before reading on below. Of course, this isn’t a masterpiece of videography nor is it intended to let you see the works in high resolution – I hope you’ll make it to see the works in person, but if you can’t, I hope you can live vicariously through my reportage! [PS follow @arttrav on Instagram for instant reports from my life and more videos like this!]

Let’s take a look in detail at some of the sections. The opening room is worth spending time in to look at the three female portrait busts on display.

Although Verrocchio was in Donatello’s workshop and working on Medici commissions in that pivotal moment in Renaissance history under Lorenzo the Magnificent, his real master in marble sculpture was Desiderio da Settignano. The curators write:

“The female portrait bust, a genre recently reinvented, became for both sculptors the most arduous and fruitful test of their aptitude, transmitted later to Leonardo as painter. After Desiderio’s early death (1464), Verrocchio remained his most important artistic heir, but, finally, no longer a compliant follower. The difference between the Frick Young Woman in New York and the Lady with Flowers expresses that between the pupil he once was and the undisputedly seminal figure that he became: the master of many, not only of Leonardo.”

In the Lady with Flowers from the Bargello, circa 1475, Verrocchio’s treatment of decorative detail like the woman’s fine headdress and the delicacy of the hands foreshadow’s Leonardo’s own studies of hands and drapery.

Famous warriors of antiquity are the theme of the second room, with a series of cameo-like marble reliefs that Leonardo must have enjoyed since he drew profile caricatures that look similar. These are put into relation with Verrocchio’s bronze David from the Bargello, the Biblical warrior. This was his first large scale bronze, a much less sexy heir to Donatello’s treatment of the same topic in bronze.

One of the two largest rooms at Palazzo Strozzi is dedicated to “Madonna paintings,” as I call them. In a line-up of mostly similar paintings, one can appreciate the quality of the Verrocchio “model” of a type that was to become very popular with contemporary artists and patrons. The curators suggest that Botticelli (here with a Madonna and Child on loan from Naples that I first mistook for a Lippi) may have been influenced by Verrochio’s Madonna prototype of this period, although no documentation exists to demonstrate that Botticeli might have frequented Verrocchio’s workshop. A second room of painting is dedicated to Pietro Vannucci, known as Perugino, who “exported” Verrocchio’s style to Umbria and then to Rome. In fact, looking back at the Madonnas of the 1470s, they exhibit that sickly sweetness I associate with Perugino (not my favourite artist, I must say), who has clearly absorbed this element from his master.

We move on to Rome in the next room, to see the influence that ancient monumental sculpture had on Verrocchio. Vasari says he made some silver statues of the Apostles for the altar of the Sistine Chapel at the same time as his students Perugino and Ghirlandaio frescoed the walls. Two heroic ancient busts in this section, by Antonio del Pollaiolo (Lorenzo Neroni, Bargello) and Verrocchio (Giuliano de’ Medici, National Gallery) are rare terracotta sculptures that speak of yet another Renaissance portraiture tradition. While the attribution of this sculpture to Verrocchio is now mostly unanimous, its function is only a hypothesis; missing from the 1496 inventory of Medici artworks, this could be an oversight, or this might be a model or unfinished work that would have held further ornaments like a metal helmet.

The extremely classical Putto with Dolphin, made for the Medici villa at Careggi and transferred to Palazzo Vecchio in the 16th century, is a culmination of the Renaissance’s embracing of ancient tropes rendered in an entirely contemporary style. I’m particularly partial to this work since I wrote my PhD dissertation on putti, and this one of the first fat and wonderful babies to have stepped out of the margins of manuscripts to hold their own in Renaissance iconography.

The chubby cherubic cheeks are nicely compared to those of the Little Boy, a marble bust by Desiderio da Settignano from the Washington National Gallery, displayed in front of the Putto with Dolphin and dating to about 15 years earlier. Desiderio’s expressive portrait reveals an ideal of childish beauty that influenced the young Verrocchio, who however blends this with an understanding of antique models in a style that moves into the High Renaissance. This comparison is a tribute to the role of teaching; Desiderio is the master of Verrocchio, who in turn becomes the master of Leonardo.

The exhibition doesn’t end here, but my narrative does. Unfortunately, I haven’t had a chance to see last next two sections at the Bargello yet. These are dedicated to two important works, the Incredulity of Saint Thomas bronze sculptural group that Verrocchio made for Orsanmichele, and the wooden cruxifix attributed to Verrocchio, taken from the deposits of the Bargello Museum where it is held for the Confraternity of San Girolamo.

Verrocchio in Florence and Tuscany

Palazzo Strozzi has a wonderful tradition of encouraging you to get out of the show (fuorimostra) and go find out more about the artist in the surrounding area. A booklet is available for free at the museum, complete with map, to guide you to finding these gems. Here is a shortlist of other places to find Verrocchio in Florence and Tuscany.

- Florence / Santa Croce: Involved in Desiderio da Settignano’s Marsuppini Tomb; Gravestone of Fra Giuliano Verrocchi; Saint John the Baptist and Saint Francis of Assisi, detached fresco by Domenico Veneziano foreshadowing Verrocchio’s painterly style.

- Florence / Church of Sant’Ambrogio: Plaque commemorating the burial of Andrea del Verrocchio, whose mortal remains were brought back to Florence from Venice, where he died, by his pupil Lorenzo di Credi, the heir to his workshop.

- Florence / Uffizi: The Baptism of Christ, painted in Verrocchio’s workshop for the Vallombrosan monastery of San Salvi, entered the Uffizi in 1919. Verrocchio designed and began painting the picture in c. 1468, possibly with Francesco Botticini’s aid, while Leonardo completed it ten years later.

- Pistoia / Forteguerri Cenotaph in the Cathedral, begun by Verrocchio.

Visitor information

Verrocchio, Master of Leonardo

Palazzo Strozzi, 9 March – 14 July 2019

The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC will host a specially curated version of the show from 29 September 2019 to 2 February 2020.

Curators Francesco Caglioti and Andrea De Marchi

www.palazzostrozzi.org

Sign up to receive future blog posts by email

Alexandra Korey

Alexandra Korey aka @arttrav on social media, is a Florence-based writer and digital consultant. Her blog, ArtTrav has been online since 2004.

Related Posts

January 30, 2024

Florence Museum News 2024

January 5, 2024

The Architecture of Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library

July 19, 2023