The beginning of November in Tuscany always comes accompanied by dramatic rains, and this year is no exception. We watch the Arno rising and annually remember the terrible flood of November 4, 1966. These seasonal rains serve as a reminder that despite our best efforts to control many things, nature, and particularly water, will always have things her way. Leonardo da Vinci was a great observer of water, of its ebbs and flows, its paths and ways to harness and deviate it. Many of these observations are written in the document now known as the Leicester Codex; this rainy season the Uffizi presents a special exhibition of the work on loan from Bill Gates, who bought it at auction in 1994. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester. Water as a Microscope of Nature will be on display from October 29, 2018 to January 20, 2019.

The Aula Magliabechiana, underneath the library of the same name, is the exhibition space on the ground floor of the Uffizi dedicated to the precious codex, displayed unbound in protective cases. The pages are accompanied by short descriptions in Italian and English, numerous videos, and other important loans to correlate the show’s thesis: that Leonardo da Vinci sees water as microcosm of the universe.

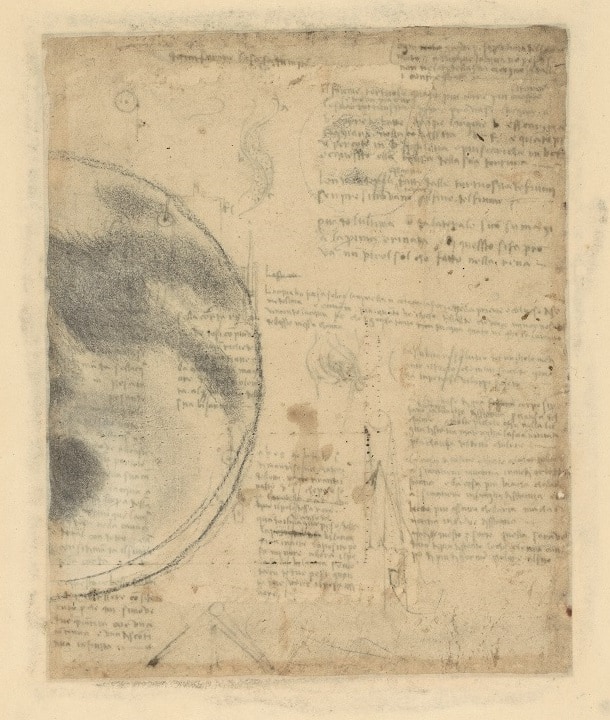

Leonardo left behind a massive corpus of written works, of which it is estimated that about half are currently known (some 7000 pages). These come in different forms, essentially drawings and loose leaves with writing or notebooks or folded papers that create a single corpus; some were bound together by the artist and others by later collectors. The Leicester Codex is composed of 18 large sheets of paper that were folded in half, creating four sides on which to write and draw, compiled to a large extent in Florence between 1504 and 1508. These were subsequently bound together. This document, along with the similarly formatted Arundel Codex in the British Library, offers much of the scientific background to Leonardo’s nature studies. The Leicester codex in particular deals with water, as well as with the phases of the sun and the moon, and is one of the less illustrated documents handed down from the great artist.

Courtesy Bill Gates/©bgC3

The presentation in the Uffizi allows you to wander through the themes treated by Leonardo in essentially your own order, which is appropriate since he didn’t write things in a particularly orderly manner; this also will work well when the show draws crowds (which I think it will), and people will need to pause and read things – it’s not the kind of stuff you can just run through.

There is a start to the exhibition to the right of the entrance: a row of beautiful illuminated manuscripts and early printed books of texts that Leonardo is known to have read or owned, addressing the question of if Leonardo was “a man without letters” as he often claimed (the answer: no). And at the end, there is a longer video you can sit down and watch.

In between, fascinating thematic sections expand on some of the pages of the Codex, such as an examination of Leonardo’s proposal for a canal from the sea to Florence via the Arno, or a look at the “dark side of the moon”.

The exhibition is high tech, well explained, and beautiful. I recommend leaving yourself two hours to visit. Despite the difficult, scientific content of Leonardo’s manuscripts, I think that children will also enjoy this show under the guidance of their parents.

The exhibition left me asking a few basic questions that I’ve tried to answer through further reading over the past few days. Firstly, what is the great appeal of these works? The mysterious looking notes from the beyond, scripted in tight mirror-writing and accompanied by marginal diagrams, have been exhibited around the world in different institutions, focusing on different documents and themes. Every exhibit is fascinating, and each requires a lot of time to read all the apparatus. They are beautiful in their own right as documents, but it’s what they say that is most important. These notes are evidence of genius, even when a good part of the content, once analyzed, has been disproven, or connected closely with Medieval precedents. But as Katrina Dean says in a presentation essay of a digital exhibition at the British Library, “later students of Leonardo’s manuscripts found his ideas to be incisive and often prescient of thinkers of the modern scientific age on a wide range of subjects, the seeds and off-shoots of a fertile mind.”

Bill Gates gets only a short line of thanks in the Uffizi’s huge and very academic catalog (which contains essays by all the topmost Leonardo scholars); in an interview with The Florentine, director Eike Schmidt said that Gates was a very private person and that he wouldn’t be talking about the loan relationship, which explains the lack of a written forward by or other mention of the owner. Gates loans the codex to one museum per year. The rest of the time, we don’t know what he does with it. One of my interns asked me a good question: why did Gates buy it? Gates bought the codex, briefly owned (from 1980) by the American industrialist Armand Hammer, in 1994 for $30.8 milion. Fast Company asked him why a few years ago and this is his answer: “It’s an inspiration that one person – off on their own, with no feedback, without being told what was right or wrong – that he kept pushing himself,” Gates says, “that he found knowledge itself to be the most beautiful thing.” The new owner is similarly obsessed with knowledge of the world in all its intricacies.

Leonardo represents lifelong learning from experience and observation as well as from books, and his codices are a unique testimony to genius.

Knowledge – and its pursuit – should never go out of style.

Visitor Information

Water as Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester

Uffizi, Aula Magliabechiana

30 October 2018 – 20 January 2019

The exhibition is included in the admission ticket to the Uffizi.

Discover the Codex Leicester on the Exhibition website

Sign up to receive future blog posts by email

Alexandra Korey

Alexandra Korey aka @arttrav on social media, is a Florence-based writer and digital consultant. Her blog, ArtTrav has been online since 2004.

Related Posts

January 30, 2024

Florence Museum News 2024

January 5, 2024

The Architecture of Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library

July 19, 2023