Our relationship with the visual arts is often emotional and personal. Most people are not able to explain what it is that they like about a given painting, in part because our education system does not provide the vocabulary with which to do so, in part because there are factors of attraction, to art as to humans, that are not entirely logical.

Art education and art history train viewers in a vocabulary and critical framework designed to substitute unlearned affinity with capable analysis. In some subjects, it may be possible to replace all emotions and enthusiasm with an analytic approach. After 14 years of study, I succeeded in reaching this level of art historical nirvana and am only now starting to recover as I have stepped away from that field. Some anonymous nighttime sessions have helped to make me feel that it is okay to just like something with my gut and not explain why in terms of art historical relevance, technical expertise, or stylistic or thematic innovation, backed up with abundant footnotes.

Nonetheless, my recovery program sponsor believes that, in the context of this assignment from the Italy Blogging Roundtable, it would be appropriate to name not one “my favorite work of art in Italy,” which is impossible for someone afflicted as I am, but three, one in each of the above-mentioned categories.

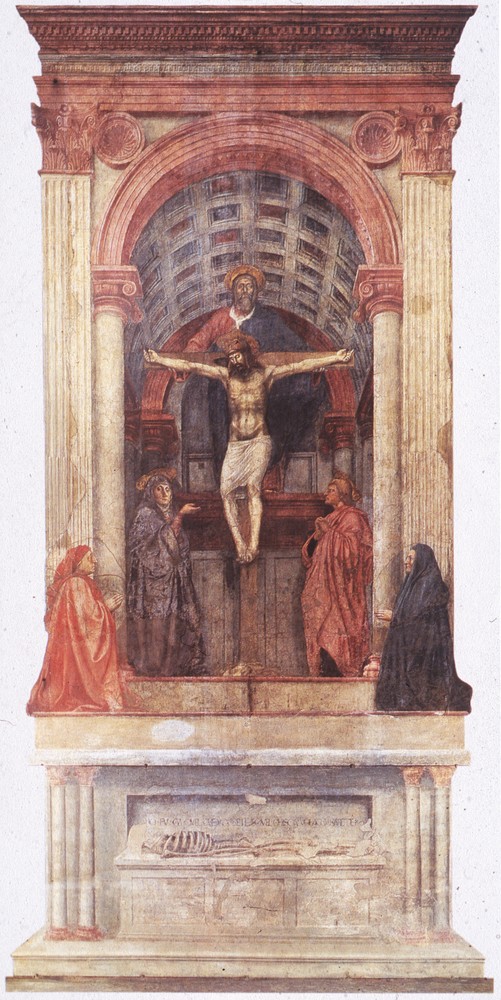

There are works that deserve our admiration for being turning points in art history. These are often the most famous exponents of any given period – Picasso’s Guernica, Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling, Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia. For the early Renaissance I have to acknowledge Masaccio’s Trinity, located inside the church of Santa Maria Novella, as a first in the use of perspective and one of the earliest exponents of this period’s fascination with mathematics. The coffered vault over the space in which the crucified Christ is depicted allows the viewer to precisely calculate the volume of that space, a party trick nowadays but a common ability for Florentine merchants who had to be able to determine the value of a barrel of wine (at that time not a standard size) with a single glance. (About this, see the fascinating art history classic Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy by Michael Baxandall, idol of my undergraduate years). My appreciation for Masaccio is an intellectual one, not an emotional one, and perhaps this is appropriate for an artist who had such a scientific approach to the study of nature that he was the first to paint shadows under his people.

There is a geographically limited moment, not a single work or artist, that for me represents the greatest technical advancement in the Italian Renaissance. Perhaps not coincidentally, paintings from the early Venetian Renaissance are also the ones to which I have the strongest emotional reaction, even during the worst throes of my neutrality disease. Giorgione, the Giorgionesque works of Giovanni Bellini, and, although later and somewhat different, certain paintings by Lorenzo Lotto share a characteristic that make me stop in my tracks and exhale. (Some might attempt to add the young Titian to this list but he doesn’t have this effect on me.)

Despite the fact that Giorgione and his closest followers did away with line in favor of hazy sfumatura, there is a calming solidity to the best of these works. In Bellini’s Madonna of the Meadow and Lotto’s Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, this solidity derives from their triangular composition (hence comforting, thanks to its wider base). We see successful experiments with mixing oils into tempera paint, and excellent chromatic choices. But one by one these factors do not logically add up to generate whatever it is that attracted me so strongly to these two works when I saw them in person (for this is an effect that I don’t get from reproductions). I did not choose to specialize in the Venetian Renaissance, and I am glad, for I prefer this sensation to remain a mystery to me.

What we study as the “progress” of art history is made up of a series of visual innovations, in the same way as our life these days is affected by a series of technical innovations, such as the one that permits me to write this post on an iPad on the beach. Some steps in stylistic or thematic change are pretty obvious, like all of a sudden the Impressionists were making fields of blotchy out of focus flowers, Hellenistic sculptors introduced drama to marble, or round arches replaced pointed ones and heralded the Renaissance.

But it is the small steps towards these changes that fascinate me more. Of course, we see these things in retrospect. One of my favourite paintings in Florence is Gentile da Fabriano’s Procession of the Magi (the Strozzi Altarpiece) at the Uffizi. What appears to be pure International Gothic style has these really exciting infiltrations of modernity. In the predella below the main scene is what we think might be the first night scene in Renaissance art. Mary and the manger are illuminated in a *consistent manner (*and that’s the relevant part here) by the light that emanates from the baby Jesus. In the main panel, Gentile also experiments with the angles of the heads of figures in the crowd. Meanwhile, this painting also has the tooled gold leaf decorative elements typical of patrons’ wishes, making this altarpiece a transitional one that successfully integrates new and old – no small challenge.

I am continuing on my path to recovery and approaching contemporary art because, having not studied it, I judge it by other factors, one of which is “would I put this in my house?” which doesn’t apply well to things like altarpieces, for obvious reasons. Traveling to cultures whose art lacks references to Western history as I know it is also helpful. But no matter what I do or where I go, I will always look at art like an art historian. It is part of who I am.

Italy blogging roundtable

This post is part of a series in which five of us challenge each other to write on the same topic, once a month. If you’ve missed them, read about why I blog about Italy and Driving in Italy. The other posts on the topic of “my favourite work of art in Italy” are:

- Gloria at At Home in Tuscany – Why I Love Tuttomondo, Keith Haring’s Mural in Pisa

- Rebecca at Brigolante – Italy Roundtable: Sliding Doors, What-ifs, and the Cross of San Damiano

- Melanie at Italofile – Five Fabulous Art Works in Rome You May Have Missed

- Jessica at WhyGo Italy – My Favorite Work of Art in Italy

Sign up to receive future blog posts by email

Alexandra Korey

Alexandra Korey aka @arttrav on social media, is a Florence-based writer and digital consultant. Her blog, ArtTrav has been online since 2004.

Related Posts

September 11, 2023

An art historian’s approach to things to do in Naples, Italy

June 22, 2023

4 day trips from Palermo up the Tyrrhenian coast

September 20, 2021