With Valentine’s Day just around the corner, let’s take a look at “love” as its shown in my art period of choice, the Italian Renaissance. You’d think it’d be easy to find artworks that represent love, but physical love was not really something to put on public display during the Early Modern age. Images of love and sex in Italian Renaissance art can be classified in three ways: metaphorical, mythological, or private imagery.

Love and sex in Italian Renaissance art

People have always had sex, but only recently have they started talking about it. The Victorian era may have been a historic extreme in terms of prudery, with erotic Greek attic vase painting being an opposite pole, but through most of Western history there is little depiction of physical love. When artistic commissions were dominated by religious subjects, obviously we weren’t going to see any thigh, so we had to wait ’til Italian Renaissance patrons invented the mythological genre (at the same time, up in Northern Europe, still no thigh for you).

Mythology

Mythology helped create excuses to show scenes of luscious females being abducted, usually by gods who take on animal form. Titian was very good at this kind of thing – his Rape of Europa, for example, shows a woman being abducted by a bull who is actually Jupiter. There is an excellent analysis of this painting on the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum website.

Another popular animal/human intercourse was that between Leda and Zeus in the guise of a swan, which was represented by both Leonardo and Michelangelo, and both of these paintings are lost (deliberately?) but known through numerous copies, attesting to their appeal at the time. The Michelangelo version was the subject of an exhibit curated by Jonathan Nelson at the Accademia a few years ago. Here is a drawing by Cornelis Bos after the lost Michelangelo, showing that the great artist cuts to the chase about the sex act, placing the swan firmly between Leda’s legs.

Art historian Irene Backus drew my attention to a modern GIF animation of the Leda and the Swan that was removed by police from a gallery in London for “condemning bestiality”, proving that this image still “causes ripples” after all these years.

One of the most fun depictions of erotic mythology is the fresco cycle by Giulio Romano commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga in 1525-6. In a private dining room, the riotous Wedding of Cupid and Psyche depicts amorous guests – I illustrate the tamest scene here.

Metaphor

The concept of love is also expressed metaphorically; here, if you’re looking for something racy and physical, you’re likely to be disappointed. The first painting that springs to mind is Titian’s allegory of “Sacred and Profane Love“. Basically, this painting is intended to express (and teach) the difference between being a slut and being the kind of woman you’d want to marry, based on a concept of twin Venuses outlined by Ficino.

Most other metaphorical expressions of love use Cupid as a symbol. Faithful friend of Venus, Cupid shoots lovers and shows up playing in just about every scene of “love”, including in Europa, above. A book published in 1608 in Northern Europe but that circulated widely in print, called Amorum Emblematum, pretty much definitively sums up everything you’d want to metaphorically say about love. In the page shown below, true love (gold) is tested by two Cupids.

![Amorum Emblemata: "Amor certus in re incerta cernitur [23]"](https://i0.wp.com/www.arttrav.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Amorum-emblemata45-700x584.jpg?resize=700%2C584&ssl=1)

For your eyes only

The printing press allowed for the diffusion of cheap and private images – private in the sense that they didn’t have to hang on the wall, not that nobody saw them! With it came racy, tongue-in-cheek treatises on sex and love – like Machiavelli’s satirical play La Mandragola published 1531.

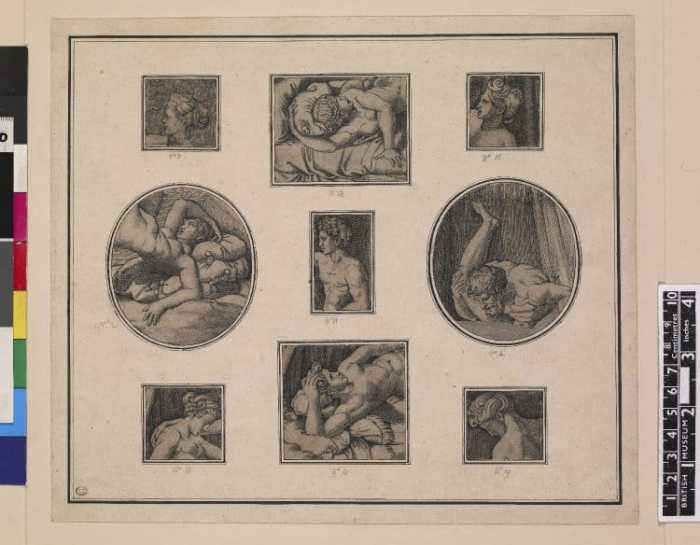

While most of these plays and treatises were not illustrated beyond perhaps a frontispiece, the most famous case of erotic engraving and equally erotic text during the 16th century is I Modi. A text that reads much like a public bathroom stall was written by the otherwise excellent poet Pietro Aretino, while engravings of the “sixteen positions” were carried out by Marcantonio Raimondi, based on a series of paintings by Giulio Romano. The book, published in 1524 and 1527, was of course banned and burned by the pope, and only fragments of the images survive. These fragments in the British Museum suffice to give us a glimpse of something that must have been very racy indeed.

Another series of engravings, Jacopo Caraglio’s The Loves of the Gods, after drawings by Rosso Fiorentino and Perino del Vaga, had greater fortune thanks to the rather transparent disguise of the subject (“gods”) – it was even praised by Vasari. Nonetheless it was no less racy than I Modi, it just had this veil of mythology superimposed on it.

There are numerous other “private” forms of erotic art that circulated. For example, the inside of cassone lids – the trunks usually placed around the bed in the Renaissance – sometimes had nudes painted on them. Sculpture, too, that was planned for more private than public display might be more risqué – Donatello’s bronze David (likely from the 1440s) was intended to be a private sculpture, and thus is much more sexy than his marble David which was for Orsanmichele (both are in the Bargello if you wish to go compare them in person). Even earlier, amusing little erotic references could be found in the margins of illustrated manuscripts, where they would only be seen by the elite men that owned them.

Paper is the private medium par excellence, so I leave you with the best love letter of all time, Michelangelo’s “presentation drawing” that he sent to Tommaso Cavalieri, for whom he claimed to have had strong Platonic love. Mythological, private and passionate, it’s probably this period’s sexiest work of art.

For further reading

A lot of good books have been written on the topic of love and sex in the Renaissance.

For a fun fictional account of the story of I Modi, check out Hellenga’s The Sixteen Pleasures

Sarah Dunant’s In the Company of the Courtesan is a well researched book set in Renaissance Venice around the Sack of Rome (1527) in which I Modi make a fictionalized appearance.

I have Alexander Lee’s book The Ugly Renaissance: Sex, Greed, Violence and Depravity in an Age of Beauty on my desk to be reviewed – it’s a thick tome, though intended to be readable by the general public. If you decide to read it, let me know what you think. I promise to get to it soon.

Another general public book that talks about some amusing aspects of sex in the Renaissance is How to Do It: Guides to Good Living for Renaissance Italians, which similar topics to those found in more academic books, but does away with footnotes and heavy-handed writing.

The “real story” can be found in the well-written and readable academic book by Bette Talvacchia Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture. While some parts may tell you more than you wanted to know, the introduction and first chapter are straight up the best thing you can read on this topic.

For visual fun, try the exhibition catalogue of the V&A exhibit from a while back, At Home in Renaissance Italy, which has fascinating sections on home life, female roles and more.

Sign up to receive future blog posts by email

Alexandra Korey

Alexandra Korey aka @arttrav on social media, is a Florence-based writer and digital consultant. Her blog, ArtTrav has been online since 2004.

Related Posts

September 11, 2023

An art historian’s approach to things to do in Naples, Italy

June 22, 2023

4 day trips from Palermo up the Tyrrhenian coast

September 20, 2021